Cultural and Indigenous Perspectives in the Arctic

The Arctic is home to a rich tapestry of Indigenous communities. These peoples have lived in the region for thousands of years, forging deep and enduring connections with the land, sea, and ice. Their cultures, traditions, and livelihoods are intricately linked to the Arctic environment, shaped by the need to adapt to its extreme and changing conditions.

Spread across multiple countries, Arctic Indigenous communities are distinct in language, tradition, and governance. Yet they share a common thread: a profound spiritual, cultural, and ecological relationship with the northern landscape that continues to inform their ways of life and worldview.

These communities have preserved rich oral histories, traditional knowledge systems, and sustainable practices that reflect a deep understanding of Arctic ecosystems. Their resilience and adaptability have enabled them to thrive in some of the planet’s most challenging environments, while maintaining their cultural identity and community cohesion.

As the Arctic gains increasing global attention, Indigenous voices are playing a growing role in shaping discussions on Arctic development, governance, and environmental stewardship. Indigenous perspectives offer invaluable insights into sustainable land use, climate adaptation, and the long-term health of Arctic ecosystems. In developing the Arctic, the land and culture of its Indigenous communities must be respected.

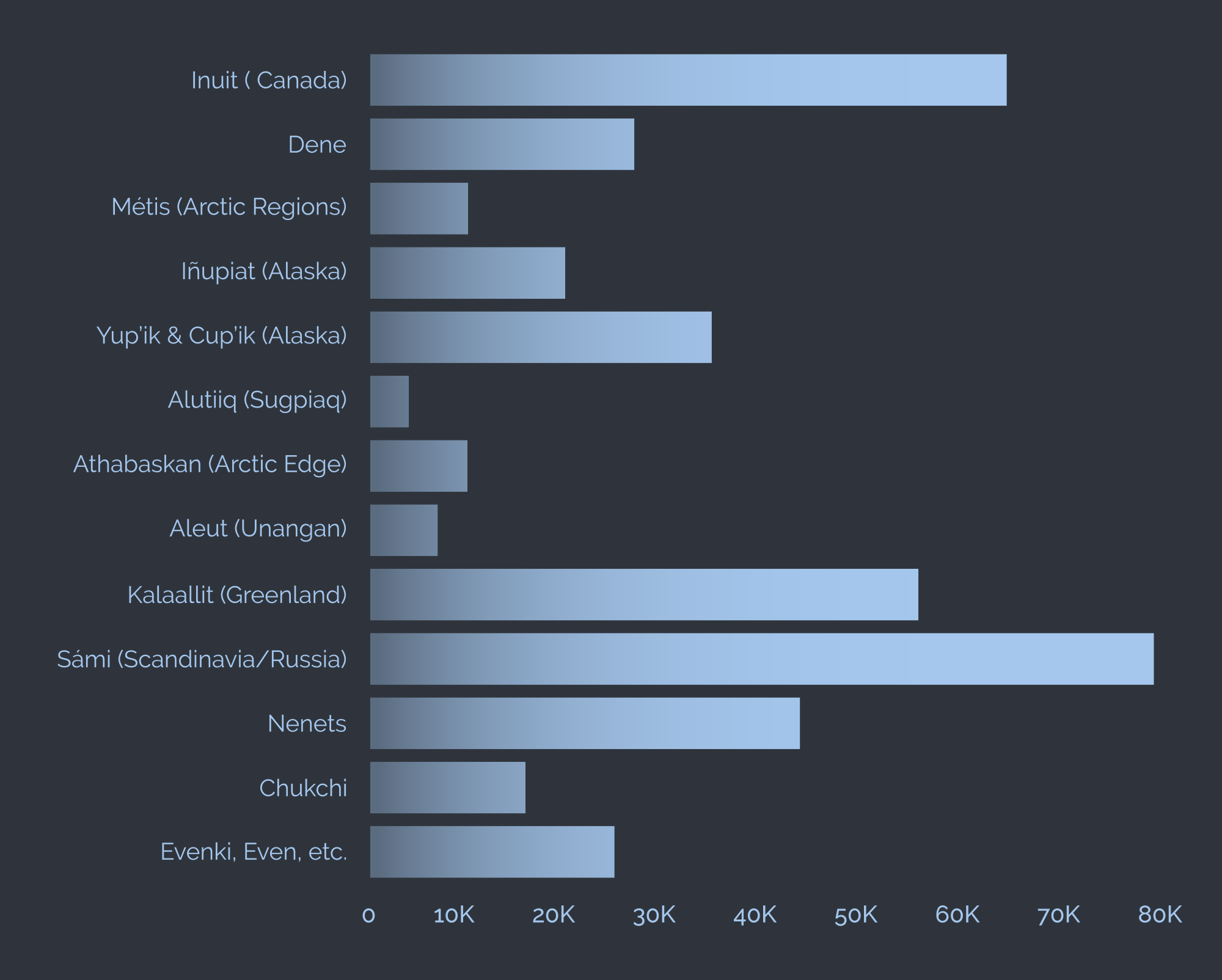

Indigenous Peoples of the Arctic by Region

Canada

- Inuit – Live across Inuit Nunangat (including Nunavut, Nunavik in Quebec, Nunatsiavut in Labrador, and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region in the Northwest Territories).

- Dene – Primarily in the subarctic regions but overlapping with Arctic areas in the Northwest Territories and Yukon.

- Métis – Some Métis communities are present near the southern Arctic boundary.

Alaska (United States)

- Iñupiat – North Slope and northwest Alaska.

- Yup’ik and Cup’ik – Western and southwestern Alaska.

- Alutiiq (Sugpiaq) – Coastal areas, particularly Kodiak and the southern coast.

- Athabaskan peoples – Mostly subarctic, but their territories border the Arctic.

- Aleut (Unangan) – Aleutian Islands, often included in broader Arctic discussions.

Greenland (Kingdom of Denmark)

- Kalaallit (Greenlandic Inuit) – Indigenous people of Greenland; culturally and linguistically related to Canadian Inuit.

Northern Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden, Finland)

- Sámi – Indigenous to Sápmi, which spans across northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula in Russia. While not all Sámi regions are strictly within the Arctic Circle, they are often included due to cultural and ecological ties to Arctic environments.

Russia

Russia is home to more than 40 recognized Indigenous groups, some of which inhabit Arctic regions. Key Arctic Indigenous peoples include:

- Nenets – Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug.

- Chukchi – Chukotka region.

- Evenki, Even, Dolgans, Yukaghir, Nganasan, and Sámi (in the Kola Peninsula) – Spread across Siberia and the Russian Far North.

The Importance of Indigenous Perspectives

Including Indigenous perspectives is essential to truly understanding the complexities of the Arctic. For thousands of years, Indigenous communities have lived in close relationship with the region’s land, sea, and climate—developing a profound connection to the environment that continues to shape their cultural identity and way of life.

Their traditional knowledge, passed down through generations, offers valuable insight into ecological patterns, wildlife behavior, and environmental change—knowledge that is often overlooked in conventional scientific or policy frameworks. As the Arctic undergoes rapid transformation, this lived experience is more relevant than ever.

Indigenous peoples are not just observers of Arctic change; they are vital contributors to discussions about the region’s future. Their perspectives are rooted in sustainability, stewardship, and respect for natural systems, making them indispensable voices in shaping responsible approaches to Arctic development, conservation, and governance.

Honoring Indigenous voices in these processes is not only a matter of cultural recognition—it is a crucial step toward ensuring that the Arctic’s future respects its heritage and remains viable for generations to come. By integrating Indigenous knowledge and leadership into decision-making, we help build a future where development and tradition can coexist in balance.

Indigenous Sovereignty and Rights

Self-Determination

Across the Arctic, Indigenous communities are actively asserting their rights to self-determination, seeking greater autonomy in managing their lands, resources, and cultural futures. This principle—recognized in international frameworks such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)—supports their ability to shape development according to their values and needs.

Organizations such as the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) and the Sámi Parliament exemplify this movement, working across national boundaries to advance Indigenous priorities in Arctic governance. These institutions represent a growing effort to ensure that Indigenous peoples are not merely consulted, but are active decision-makers in policies that directly affect their communities, territories, and ways of life.

Land and Resource Rights

Land and resource rights are central to Indigenous sovereignty, especially in the Arctic where traditional territories are deeply tied to identity, survival, and cultural continuity. Indigenous peoples across the region depend on subsistence activities such as hunting, fishing, and herding—practices that require both access to and stewardship over their ancestral lands and waters.

Progress in legal recognition has taken different forms across Arctic states. In Canada, landmark land claims agreements—such as those in Nunavut and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region—have granted Inuit communities control over vast territories, enabling them to manage natural resources, protect cultural heritage, and direct economic development. Similarly, Greenland’s self-rule arrangement has provided significant autonomy to Kalaallit Inuit, including authority over resource governance and domestic policy.

These frameworks are critical to preserving Indigenous livelihoods and ensuring that resource development is aligned with traditional knowledge, sustainability, and community values.

Participation in Governance

Meaningful participation in governance is a foundational element of Indigenous rights in the Arctic. Indigenous communities have achieved formal representation in international and regional decision-making processes, most notably through their role as Permanent Participants in the Arctic Council. This unique status gives Indigenous organizations a consistent and recognized voice in shaping Arctic policy.

Through this participation, Indigenous peoples contribute to discussions on environmental protection, sustainable development, and cultural preservation to ensure that policies reflect the lived realities and long-standing expertise of Arctic communities. Their inclusion has become an essential model of co-governance, highlighting the importance of equitable partnerships in addressing the challenges and opportunities of a rapidly changing Arctic.

Traditional Knowledge and Its Role in the Arctic

Environmental Stewardship

Indigenous knowledge, often recognized as Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), plays a crucial role in environmental stewardship across the Arctic. Rooted in generations of lived experience, TEK reflects a deep understanding of Arctic ecosystems, seasonal patterns, and long-term environmental change. Unlike short-term observational data, this knowledge captures nuanced relationships between people, animals, weather, and land—relationships that are shaped by daily survival and cultural practices.

TEK provides insights that are complementary to scientific research, offering a broader context for interpreting data and predicting environmental trends. As the Arctic experiences unprecedented ecological shifts due to climate change, traditional knowledge is increasingly being integrated into environmental assessments, wildlife management strategies, and policy-making processes. Its inclusion helps ensure that decision-making is grounded not only in modern science but also in the practical, place-based wisdom of those who know the land best.

Sustainable Practices

Many Indigenous communities in the Arctic have sustained their ways of life for thousands of years through carefully balanced, sustainable practices in hunting, fishing, and land use. These practices are based on a deep respect for nature and a guiding principle of taking only what is needed, ensuring that ecosystems remain viable for future generations.

This form of stewardship emphasizes renewal, conservation, and reciprocity. It prioritizes resource management that maintains biodiversity, avoids waste, and supports the health of the entire ecosystem. In today’s context of resource pressure and environmental degradation, these traditional approaches offer powerful models for how to manage Arctic resources responsibly and ethically. They also highlight the importance of cultural continuity in maintaining sustainable relationships with the environment.

Collaboration with Scientists

In recent years, collaboration between Indigenous communities and scientific researchers has become an important pathway for advancing Arctic knowledge. These partnerships recognize that traditional knowledge systems and scientific inquiry can mutually enrich one another, leading to a more holistic understanding of the region.

Indigenous observations are vital in tracking wildlife migrations, ice stability, seasonal shifts, and climate-related disruptions. This locally specific information may not be captured by remote sensing or intermittent fieldwork. By including Indigenous voices in research design, data collection, and interpretation, scientists can produce more accurate, culturally relevant, and community-informed outcomes.

Such collaborations also build trust and mutual respect, allowing both scientific and Indigenous knowledge systems to contribute to adaptive strategies, policy planning, and long-term monitoring in the Arctic.

Cultural Heritage and Preservation

Language and Storytelling

Indigenous languages across the Arctic are not only means of communication but vital carriers of cultural identity, worldview, and ancestral knowledge. Each language holds unique ways of understanding the environment, relationships with the land, and values passed down through generations. Oral storytelling traditions, embedded in these languages, serve as powerful tools for teaching history, ethics, and survival skills in the Arctic landscape.

Recognizing the urgency of language loss, many Indigenous communities are leading preservation and revitalization efforts. These include language immersion programs for children and youth, digital archives of spoken word and traditional stories, and educational initiatives that bring elders and language experts into schools and communities. Through these efforts, Arctic Indigenous peoples are reclaiming and strengthening their linguistic heritage as a core pillar of cultural continuity.

Art and Traditions

Indigenous art and traditional practices are vibrant expressions of cultural heritage and identity in the Arctic. Through carving, weaving, beadwork, and printmaking, artists convey stories of survival, spirituality, and connection to nature—drawing inspiration from the region’s wildlife, landscapes, and lived experiences.

Traditional lifeways such as seal hunting, fishing, and reindeer herding are more than just economic activities; they are deeply embedded in social values, community cohesion, and intergenerational knowledge transmission. These practices are often performed in accordance with cultural protocols and seasonal rhythms, maintaining a respectful relationship with the environment.

Resilience Amid Change

As the Arctic faces growing pressures from climate change, resource development, and globalization, Indigenous communities are actively working to preserve their cultural identities while adapting to a rapidly evolving world. This resilience is reflected in their ability to blend traditional knowledge with modern technologies, creating new ways to support cultural survival and self-reliance.

From using drones to track caribou migrations to employing digital tools for language learning and storytelling, Indigenous peoples are innovating to ensure their cultures thrive in the 21st century.

In the face of uncertainty, Arctic Indigenous communities remain deeply committed to honoring their heritage, protecting their knowledge systems, and shaping a future in which culture, environment, and identity are mutually sustained.

Challenges Faced by Indigenous Communities

Climate Change Impact

Climate change poses an urgent and direct threat to Indigenous communities across the Arctic, where melting ice, shifting ecosystems, and unpredictable weather patterns are disrupting ways of life that have been sustained for generations. Traditional practices such as hunting, fishing, and herding are becoming increasingly difficult to maintain, as species migrate, sea ice becomes unreliable, and seasonal cycles become less predictable.

These changes not only affect food security and economic self-sufficiency, but also threaten the cultural foundations of Arctic Indigenous societies. Traditional knowledge, spiritual practices, and community identities are often rooted in the land and climate, and when those environmental systems shift dramatically, so too does the ability to pass down cultural knowledge and maintain traditional livelihoods. Adapting to these changes while preserving cultural continuity remains a profound challenge.

Development Pressures

The Arctic is increasingly viewed as a region of economic opportunity, leading to the expansion of industrial projects such as mining, oil and gas extraction, and shipping routes. While these activities often come with significant social and environmental costs—especially for Indigenous communities whose lands, waters, and traditional territories are most directly affected.

Development can disrupt ecosystems, restrict access to hunting and fishing grounds, and damage sacred or culturally significant sites. Indigenous groups are frequently placed in the difficult position of weighing economic development against the preservation of culture, environment, and sovereignty. Ensuring that Indigenous communities have the authority and support to make decisions on their own terms is vital to addressing this challenge in a fair and sustainable way.

Social and Economic Inequities

Despite their resilience and cultural strength, many Arctic Indigenous communities continue to face persistent disparities in access to essential services such as education, healthcare, housing, and infrastructure. These inequities can intensify the impact of external pressures like climate change and industrial development, making it more difficult for communities to adapt or advocate effectively for their needs.

Limited access to quality education and healthcare affects overall well-being and can undermine community efforts to sustain traditional practices, languages, and governance systems. At the same time, inadequate infrastructure—such as roads, internet access, or clean water—can isolate communities from both economic opportunities and the broader decision-making processes that shape the Arctic’s future.

Addressing these social and economic gaps is a critical step toward empowering Indigenous communities to navigate change, assert their rights, and build a future that is both culturally and materially sustainable.

Global Recognition and Collaboration

In recent decades, Indigenous organizations from the Arctic have emerged as influential voices in shaping global understanding of the region’s environmental, cultural, and political dynamics. As the Arctic gains increasing attention due to climate change, resource development, and geopolitical interest, Indigenous communities have insisted—and rightfully so—that they must be recognized not only as stakeholders but as rights-holders and knowledge-bearers whose involvement is essential for just and effective decision-making.

Through coordinated efforts and long-standing networks, organizations such as the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC), the Saami Council, and the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) have become key participants in international forums, including the Arctic Council, the United Nations, and global climate summits. These organizations advocate for the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge systems, sustainable development models rooted in cultural values, and the protection of Indigenous lands, rights, and ways of life.

Their growing presence has led to greater international recognition of the unique perspectives and contributions Indigenous peoples bring to conversations about climate resilience, biodiversity conservation, and regional governance. Collaborative approaches between states, scientific institutions, and Indigenous organizations are increasingly seen not just as a moral imperative, but as a practical necessity for managing the Arctic in a time of rapid transformation.

Advocacy on the International Stage

Arctic Indigenous leaders are actively engaging in global advocacy, pushing for policies and agreements that protect their rights, cultures, and environments. Their presence at major gatherings—such as the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)—has brought visibility to the specific challenges their communities face, such as climate displacement, environmental degradation, and threats to food security and cultural survival.

These advocacy efforts focus on ensuring that Indigenous peoples are not sidelined in conversations that impact their homelands. Instead, they demand that Indigenous voices shape those discussions, policies, and solutions. A central tenet of this advocacy is the recognition of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC)—a principle that guarantees Indigenous communities the right to participate fully and voluntarily in decisions affecting their lands and resources.

By advocating for climate justice, cultural rights, and sovereign decision-making, Indigenous leaders are building coalitions and shaping policies that extend well beyond the Arctic, influencing global approaches to equity, sustainability, and Indigenous rights.

Cultural Exchanges and Global Awareness

While Indigenous political engagement continues to grow, so too does the global appreciation for Arctic Indigenous cultures, thanks to vibrant cultural exchange initiatives. Festivals, art exhibitions, and cultural programs are bringing Indigenous expressions—from storytelling and performance to visual arts and craftsmanship—to audiences around the world.

These cultural events celebrate the diversity, creativity, and resilience of Arctic Indigenous peoples. They also serve as powerful tools for building cross-cultural understanding, breaking down stereotypes, and fostering dialogue between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. Whether through traditional Sámi joik singing, Inuit sculpture and printmaking, or Chukchi dance and dress, these cultural expressions invite broader society to witness the deep beauty and enduring strength of Arctic traditions.

Cultural exchanges also help strengthen Indigenous identity, especially among youth. As young Indigenous people engage in global networks, showcase their heritage, and participate in cross-cultural learning, they gain a sense of pride and purpose that helps bridge traditional knowledge with contemporary life.

Together, these efforts in global collaboration, international advocacy, and cultural exchange reflect a powerful movement: Arctic Indigenous peoples asserting their rightful place on the world stage.

Together, these efforts in global collaboration, international advocacy, and cultural exchange reflect a powerful movement: Arctic Indigenous peoples asserting their rightful place on the world stage—not only to protect their homelands and rights, but to contribute meaningfully to the global dialogue on how we live, govern, and care for the planet we share.